In 1945, the use of nuclear weapons on Nagasaki and Hiroshima introduced the world to the devastating potential of atomic warfare and diverging power dynamics. America’s new devastating weapon forced Japan to surrender, signaling the end of the war. After WWII, the U.S. and the Soviet Union rose to world superpower status. Clashing political and economic ideas between these two nations set the stage for the Cold War, the next global conflict still felt today in many ways. A significant byproduct of the Cold War was the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM)—unmanned weapons that utilized nuclear warheads. ICBMs had the capability to strike targets across the globe within a matter of hours with unbelievable destructive power that exceeded weapons previously used in war.

X-10 used in research and development test of the SM-64 assigned to OOAMA June 4, 1957. Cancelled July 12, 1957

Both countries during the Cold War amassed large nuclear arsenals for the dual purpose of threatening the other, and at the same time, as deterrents to dissuade the other from overt aggression. Both countries’ build-up of nuclear firepower discouraged either country from engaging in direct conflict with the other based on the fear that both countries had the ability to completely annihilate each other. This principle of mutually-assured destruction encouraged the U.S. to constantly develop new and cutting-edge ICBM technology in hopes of securing the country’s defense against the Soviet Union during this arms race.

For more than 70 years, Hill Air Force Base has been vital in the research, development, support and maintenance of the country’s ICBM arsenal, and continues to be a crucial asset to the nation’s nuclear posture in this modern era.

Ushering in the Nuclear Age

SM-62 “Snark” missile arriving at Hill AFB for repair Nov 6, 1957

Hill Field began its storied history with missiles when it received responsibility for inspecting and testing captured German V-1 rockets at the end of WWII. The information gained from the V-1 rockets by Hill Field’s Ogden Air Depot played an integral part in laying the foundation to develop what would later become ICBMs. Thanks to the testing and inspection of these weapons, the U.S. Air Force developed the Northrop B-62 “Snark” missile, and on September 18, 1952, the Ogden Air Depot began supporting the Snark , the nation’s first operational intercontinental cruise missile. It utilized a nuclear warhead and solid propellant fuel to deliver payloads within a respectable range of approximately 5,000 miles. Thanks to the Snark’s noteworthy performance, in 1959, the Strategic Air Command activated the 702nd Strategic Missile Wing at Presque Isle Air Force Base in Maine.

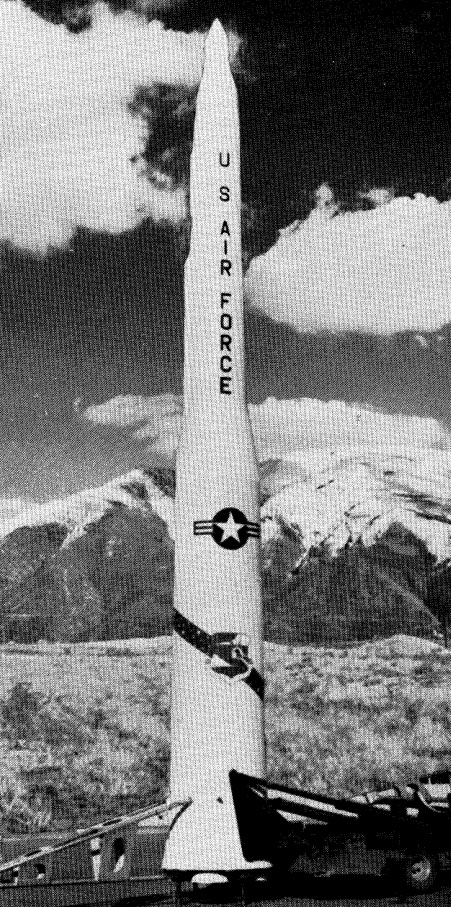

OOAMA model of SM-80 Minuteman Jan 6, 1959

By 1960, the Ogden Air Material Area (OOAMA) had complete logistical and maintenance responsibilities over the nation’s first intercontinental missile. Another early missile project briefly supported by the OOAMA was the SM-64 “Navaho,” beginning shortly after WWII. It envisioned an air-breathing, nuclear-capable missile that had a range of 1,000 miles. The program also aimed to further improve on the Navaho by upgrading to an air-launched version with a 1,700-mile range and a surface-launched version with a range of 5,500 miles.

By the time OOAMA assumed responsibility for the program in 1957, the Navaho program was eight years behind schedule. Leadership canceled the program approximately a month later. The Snark’s lifetime was also short-lived. By March 1961, less than one month after the 702nd reached full operational capabilities, President John F. Kennedy directed that the missile be phased out in favor of the superior Atlas and Titan ICBMs.

The First Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The late 1950s saw the development of the first ICBMs accelerate as the arms race heated up. In October 1959, the Atlas, the country’s first land-based, nuclear-tipped, intercontinental ballistic missile, went on full alert. While it was the first ICBM deployed, the Atlas was never intended to be the only strategic missile the country utilized. The Atlas and Titan I ICBMs were developed concurrently beginning in 1955. While both missiles improved on the capabilities of the SM-62 Snark, the Titan I aimed to be an improvement on the Atlas’ range, travel speed and warhead size. The Eisenhower administration wanted both weapons developed at the same time in case the Atlas experienced delays in development. By 1962, the number of Atlas missiles active around the country was 125. Less than three years later, however, the Atlas retired from service as the Titan I eclipsed the Atlas and Snark in range, nuclear payload and speed. Similar to the Atlas, though, the Titan I served only three years.

As the Titan I began to phase out, its replacement came in the development of the gargantuan Titan II. The Titan II was the U.S.’ largest deployed ICBM—standing at 103 feet tall and weighing an impressive 330,000 pounds. Fifty-four Titan IIs deployed across the country and remained active until 1987.

At a Minute’s Notice

America’s nuclear arsenal was forever changed with the development of the Minuteman. This weapon was a technological marvel thanks to its improvements on previous ICBM technologies. Currently in its third iteration, the Minuteman remains a cornerstone of the nation’s nuclear arsenal to this day. The program began with the Minuteman I which carried a smaller nuclear payload than the Titan II. However, it improved on its predecessors’ capabilities by using solid fuel rather than liquid fuel, as used by the Atlas and Titan ICBMs. Liquid fuel had corrosive characteristics and could not remain in missiles for extended periods of time. Whenever the Atlas or Titan ICBMs were ready to launch, there would be a longer delay between the time a launch order was issued and the actual launch due to the fact that the missiles needed to be fueled. Conversely, the Minuteman utilized solid fuel that could remain in the missile almost indefinitely, meaning it only took about a minute for the Minuteman to launch from the time it received the order. Thanks to this innovation, the Minuteman has remained a staple of the U.S.’ nuclear arsenal since its activation in 1962.

America’s nuclear arsenal was forever changed with the development of the Minuteman. This weapon was a technological marvel thanks to its improvements on previous ICBM technologies. Currently in its third iteration, the Minuteman remains a cornerstone of the nation’s nuclear arsenal to this day. The program began with the Minuteman I which carried a smaller nuclear payload than the Titan II. However, it improved on its predecessors’ capabilities by using solid fuel rather than liquid fuel, as used by the Atlas and Titan ICBMs. Liquid fuel had corrosive characteristics and could not remain in missiles for extended periods of time. Whenever the Atlas or Titan ICBMs were ready to launch, there would be a longer delay between the time a launch order was issued and the actual launch due to the fact that the missiles needed to be fueled. Conversely, the Minuteman utilized solid fuel that could remain in the missile almost indefinitely, meaning it only took about a minute for the Minuteman to launch from the time it received the order. Thanks to this innovation, the Minuteman has remained a staple of the U.S.’ nuclear arsenal since its activation in 1962.

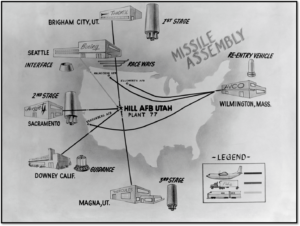

Hill Air Force Base’s experience with previous missiles like the Snark and Navaho, along with the base’s proximity to manufacturers and testing ranges made the installation the natural candidate to receive responsibilities for the Minuteman weapon system. In January 1959, OOAMA received various program responsibilities for the missile. Furthermore, production of the Minuteman occurred at Hill and with that came an economic opportunity for the state of Utah. Thiokol Chemical Corporation, which had a solid propellant plant near Brigham City, and the Utah-based Hercules Powder Company, were both among the various entities that received contracts for manufacturing the Minuteman ICBM. Various other contractors manufactured the different parts of the Minuteman in other locations. Once all the pieces were ready, they were shipped to Boeing Company’s Plant 77. Located on Hill Air Force Base, this six-building complex was located on the installation’s West Area and was built specifically for Minuteman production in 1960. Along with the building of this new plant, the Wendover Range Complex received updates and improvements to further assist in development of ICBM projects.

Although production of the Minuteman officially ended December 1978, Hill Air Force Base continues to provide support for the program. The 309th Missile Maintenance Group and the Minuteman III Directorate on base are responsible for weapon system management, logistical support and overall maintenance of the latest iteration of the Minuteman, the Minuteman III. The Minuteman III continues to be the only land-based ICBM in the nation’s nuclear arsenal and receives extensive life extending services in order to keep components of the missile viable beyond 2023.

Sentinels on the Horizon

US Air Force artist’s rendering of the Sentinel in flight

As the world’s geopolitical landscape changes, the U.S. will continue to adopt new and innovative strategies for its nuclear defense policy. When it is time for the aging Minuteman III to phase out, the modernized Sentinel missile program being developed by the Northrop Grumman Defense Company will replace it. The Sentinel program aims to keep the land-based leg of the country’s nuclear triad viable for the next 70 years.

Once Minuteman III is phased out, Hill Air Force Base will continue to play a crucial role in maintaining our nation’s ICBM fleet. For one, the Sentinel Systems Directorate has and will continue to provide total program oversight of the new missile system. Collaborating with the Directorate is Northrop Grumman, who is developing this cutting-edge technology. Lastly, the 309 MMXG is postured to support whatever ICBM maintenance and repairs this new weapon system will require. Together, Hill’s ICBM support entities have, and will play, a monumental role in the improvement of the nation’s nuclear defense strategy.

Conclusion

America’s relationship with the Soviet Union during the Cold War forced the U.S. to continually adapt its arsenal to address the threat of nuclear war. Hill Air Force Base’s contributions to early missile projects and the Minuteman program highlights the base as an important factor in activating the intercontinental ballistic missiles that the country would and still depends on for nuclear deterrence. Once the Minuteman became the staple of America’s national defense, the support Hill Air Force Base provided, and continues to provide for the program, was crucial for maintaining the land-based leg of the nation’s nuclear triad.

References

Hill’s ICBM History, Ogden Air Logistics Center, Hill Air Force Base, Utah.

https://www.northropgrumman.com/wp-content/uploads/Sentinel-Fact-Sheet-.pdf

https://www.nps.gov/articles/icbm-evolutions.htm

https://www.nps.gov/articles/minuteman-icbm.htm

Ogden ALC ICBM beginnings, 75ABW/HO.