An MQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial vehicle takes off from Creech Air Force Base. (U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Brian Ferguson)

In the not-so-distant past, before toilet paper shortages and social distancing became the new normal, the Hill Aerospace Museum received its latest collection piece: an MQ-1 Predator Drone. And while we will not go into specifics about Museum workers and volunteers putting the Predator together—think kids on Christmas morning—we will tell you a little about the Predator’s history, as well as how it changed modern warfare for the U.S Air Force.

So, What is the Predator?

Before its retirement from service in 2018, the Predator Drone was a multi-mission, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)—meaning an aircraft with no onboard crew or passengers. General Atomics Aeronautical Systems built the Predator to meet the Department of Defense requirement for a long-endurance, remotely-piloted aircraft (RPA) that could fly at medium altitudes while providing surveillance for its controllers on the ground. The Predator was originally designed as a reconnaissance aircraft and was designated RQ-1. (“R” for reconnaissance, “Q” for remotely piloted aircraft.) In 2002, when the U.S. Air Force outfitted the Predator with AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, its designation changed to MQ-1, the “M” referring to multi-role.

Student sensor operators from the 6th Reconnaissance Squadron practice tactical operations during an MQ-1 Predator super sortie simulator mission at Holloman Air Force Base. (U.S. Air Force photo/Senior Airman BreeAnn Sachs)

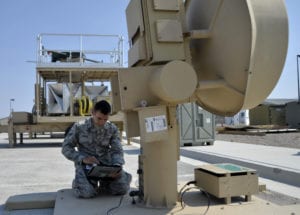

The Predator was part of a remotely-piloted aircraft system that included sensor/weapon-equipped aircraft, a ground control station and a satellite link, as well as operational and maintenance crews. A rated pilot controlled the aircraft, and an enlisted crew member operated the sensors and weapons—all from inside a ground control station. The crew remained connected to the Predator via a data link that provided line-of-site, and a satellite link that provided data for operations beyond line-of-site. However, UAVs weren’t always so sophisticated, especially when first used in military operations. Let’s take a quick look at the history of drones.

A Little UAV Background

At the end of WWII, General Henry “Hap” Arnold said, “We have just won a war with a lot of heroes flying around in planes. The next war may be fought by airplanes with no men in them at all…. Let’s go to work on tomorrow’s aviation. It will be different from anything the world has ever seen.”[1] Little did Arnold know just how accurate his statement would be.

Kettering Aerial Torpedo “Bug” at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (U.S. Air Force photo)

The first functioning, unmanned aerial vehicle actually flew prior to WWII. Known as the Kettering Torpedo “Bug” and developed in 1918, this aircraft was the forerunner to present-day cruise missiles. The Kettering was a wooden biplane powered by a four-cylinder, 40-horsepower Ford engine and carried a 180-pound bomb. It was launched from a four-wheeled dolly that ran down a portable track and used gyroscopic controls to guide it to its target. Although WWI ended before the Kettering could be used in combat, its technology was an important step forward in developing UAVs.

Radioplanes and Firebees

Norma Jeane Dougherty, later known as Marilyn Monroe, working at the Radioplane factory in 1945. (U.S. Air Force photo)

In the 1930s, the U.S. Navy developed the Curtiss N2C-2—controlled remotely from another aircraft and used as an anti-aircraft artillery target. Around the same time, the British military developed the “Queen Bee” radio-controlled aerial target, which is where the term “drone” is thought to have originated.[1] Allied Forces used radio-controlled aircraft as targets throughout WWII. Among these were the Radioplane OQ-2, the first mass-produced UAV built for the U.S. military.

In the 1950s, Ryan Aeronautical Company, which later became part of Northrup Grumman, built the Firebee, becoming one of the most widely-used target drones built. The Firebee served in a variety of roles during the Vietnam War, including reconnaissance, intelligence gathering, electronic countermeasures, and psychological warfare operations.

Ryan Firebee Drone Launch, Tyndall Air Force Base. (U.S. Air Force Photo)

Vietnam marked the first time the U.S. military deployed reconnaissance UAVs on a large scale in combat. However, drones didn’t become a mainstay of U.S. military defense until the 21st century. The development of the MQ-1 Predator helped make that happen.

Origins of the Predator

Predator drone at Tallil Air Base, Iraq. (US Air Force photo/Suzanne Jenkins)

Development of the Predator actually began in the 1980s. The decade that brought us big hair parachute pants, and Punky Brewster also brought us improved unmanned aerial technology. Aerospace engineer and Israeli immigrant Abraham E. Karem built the first Predator prototype, the “Albatross”, in his garage. General Atomics Aeronautical Systems later bought Karem’s company, the CIA awarded them a contract to build an unmanned reconnaissance aircraft, and the Predator was on its way to changing the way the U.S. Air Force fought war overseas.

In 1996, the Department of Defense chose the U.S. Air Force to operate the Predator, and the drone entered combat over the skies of Bosnia. By the late 1990s, the Predator was equipped with a live satellite video link and a laser designator to illuminate targets and guide weapons dropped from other aircraft. Increased concern over the rising threat of al Qaeda, however, led to arming the Predator with AGM-114 Hellfire missiles in 2001.

MQ-1 Predator Drone flies above the flight line at Creech Air Force Base. (U.S. Air Force photo/Senior Master Sgt. Cecilio Ricardo)

When the U.S. Air Force first tested the Predator’s missile capabilities in 2001, they had only 90 non–target drone UAVs, 15 of which were Predators. Just 14 years later, the military had almost 11,000 UAVs in its inventory. Since its first overseas deployment, the Predator has served in conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Libya, and Somalia.

Design Features

Predator Drone in shipping Container, Holloman Air Force Base (U.S. Air Force photo/Staff Sgt. Chris Flahive)

To give you some sense of the Predator’s size, it weighed 1,130 pounds empty—less than an economy car. It was 27 feet long and had a wingspan of 55 feet. The Predator had a four-cylinder, Rotax 914 engine, the same type commonly found in snowmobiles. It was armed with two laser-guided, Air-to-Ground Hellfire missiles—one mounted under each wing—as well as cameras and synthetic aperture radar. Its cruising speed was 87mph and it could fly at altitudes of up to 25,000 feet, remaining in the air for up to 24 hours fully loaded. The Predator could also be disassembled and placed into a box called a “coffin” for transportation. It was usually transported by the C-130 Hercules.

(U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Christian Clausen/Released)

A Unique Platform for a Unique War

Although the Predator’s design was not that rugged, it offered a major advantage over fighter jets: its ability to loiter for long periods of time over enemy positions and collect real-time data in, without posing any danger to its controllers on the other side of the world. Fighter jets usually arrive over a dynamic scene, deliver large amounts of ordinance, then quickly exit. The Predator, on the other hand, could collect intelligence on enemy targets over extended periods of time, “eavesdrop on enemy communications, provide troops on the ground warning of enemy movements, and give commanders an overhead view of the battlefield”.[1] The Predator gave its controllers a clearer sense of what was actually happening on the ground, and could actually fire on targets, if necessary.

An MQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial vehicle and F-16 Fighting Falcon return from an Operation Iraqi Freedom combat mission. (U.S. Air Force photo/1st Lt. Shannon Collins)

These features made the MQ-1 pivotal in fighting the Global War on Terror. The War on Terror is unlike any war that was fought in the past because it’s a war with no specific boundaries, it’s “waged against the possibility of something happening”, and there is no clear beginning or end.[2] And instead of engaging enemies on battlefields, the U.S. military fights terrorist organizations and insurgents who can blend in with local civilian populations. For this reason, the Predator’s ability to not only to gather intelligence, but also to target a single individual, made it indispensable for the type of warfare the U.S. engages in today.

Hill AFB’s Tie to the Predator Drone

So what was Hill AFB’s tie to the Predator? In 2004, the U.S. Air Force used the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR) to test the Predator’s ability to strike a moving target. Crew members guided the drone remotely from Indian Springs, NV, and successfully struck two moving tanks. The Ogden Air Logistics Complex at Hill also provided software development /sustainment in support of this drone.

Hill Aerospace Museum’s Drone

And that brings us to the MQ-1B Predator Drone currently on display at Hill Aerospace Museum. This Predator first flew on 31 January, 2005, and then was later assigned to Indian Springs Auxiliary Field, Nevada, (which later became Creech AFB). During its service life, this Predator took part in combat sorties in Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan. After flying 28,069 hours and over 1,600 combat sorties, it retired from service in 2017.

[1] Terdiman, Daniel. “The history of the Predator, the drone that changed the world (Q&A).” 20 Sept., 2014. Cnet, https://www.cnet.com/news/the-history-of-the-predator-the-drone-that-changed-the-world-q-a/ Accessed 16 Apr., 2020.

[2] Raz, Guy. “Defining the War on Terror.” 1 Nov., 2006. NPR, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/ story.php?storyId=6416780. Accessed 16 Apr., 2020.

[1] Budanovic, Nikola. “The Early Days Of Drones – Unmanned Aircraft From World War One And World War Two.” 23 July, 2017. War History Online, https://www.warhistoryonline.com/military-vehicle-news/short-history-drones-part-1-m.html. Accessed 20 Apr., 2020.

[1] Spinetta, Lawrence. “Secrets Behind the Surprising Rise of Drones.” Historynet, https://www.historynet.com/the-rise-of-unmanned-aircraft.htm. Accessed 2 Apr., 2020.