During a warm October day high above the California desert in 1947, a B-29 Superfortress dropped an experimental aircraft from its bomb bay. The four-rocket-propelled Bell X-1 piloted by U.S. Air Force Capt. Chuck Yeager only had a few minutes’ worth of fuel. The goal of the flight? Pioneer supersonic flight.

Barriers

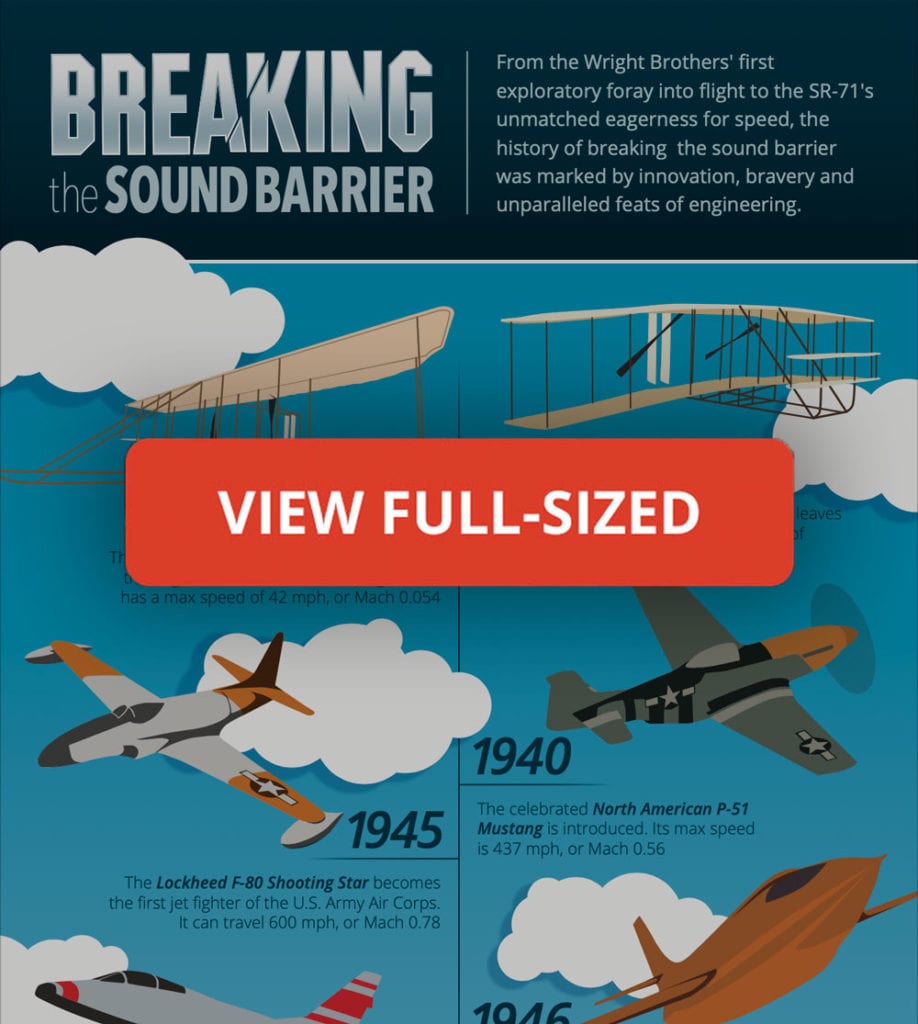

Breaking the sound barrier took undeniable courage and bravery. Since the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903, it was a commonly held belief that doing so would simply destroy an aircraft. And this belief wasn’t entirely without merit.

During World War II, pilots reported “mysterious forces” that froze their controls or broke pieces of their aircraft during high-speed dives. The pilots said it was as if they had hit a “brick wall in the sky.” Thus, the legend of a sound barrier—an actual physical barrier preventing supersonic flight—was born.

This angst was further stoked by a highly publicized incident in 1946. British test pilot Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. was killed while testing an experimental jet-powered aircraft, dubbed the “Swallow,” in preparation for an attempt to break the mythical sound barrier. The aircraft completely disintegrated during a high-speed dive.

De Havilland’s body washed up in the Thames River 10 days later. The incident crippled the British supersonic program.

But America’s own attempt was too far advanced to simply abandon. And only weeks after the British pilot died aboard the Swallow, on Aug. 29, 1947, the Bell X-1 made its first powered flight in the pursuit of supersonic flight with Yeager at the controls above the California desert.

Mach 1

Since the speed of sound varies by altitude and weather, the most useful measure of breaking it is a Machmeter. After studying artillery shells, Ernest Mach, an Austrian scientist, discovered the phenomena associated with the speed of sound and invented the Machmeter, which indicates the ratio of the airspeed to the speed of sound. The speed of sound ranges from 760 mph at sea level to approximately 660 mph at 36,000 feet.

No matter the elevation or weather, breaking the sound barrier simply means pushing the Machmeter’s needle to Mach 1.

Breaking Barriers

The Air Force wisely decided to gradually push their test aircraft to Mach 1 through a series of successive flights. On its first flight, the Bell X-1 reached Mach 0.85. Yeager piloted it to a Mach 0.89 on his second flight. On the fourth flight, the airplane reached Mach 0.91. The fifth brought it to Mach 0.925. You get the idea.

Bell X-1 in flight

Bell X-1 in flight

On the eighth flight, the aircraft pushed up to Mach 0.997, but it wasn’t without near catastrophe. Yeager lost control of the X-1’s elevator, effectively rendering the aircraft uncontrollable. It appeared, at least for a moment, as if the legendary physical barrier to break the speed of sound was more than mere legend. However, a contingent stabilizer implemented by the team of aircraft engineers saved the plane and Yeager.

Four days later, on Oct. 14,1947, the 24-year-old Yeager flew the Bell X-1 into the history books. “I thought I was seeing things,” Yeager would later write about seeing the Machmeter needle creep past Mach 1. “We were flying supersonic! And it was as smooth as a baby’s bottom.” The plane broke the speed of sound—evident to the team eight miles below who witnessed the first-ever sonic boom—and stayed there for approximately 20 seconds before Yeager shut down two of the four engines and landed.

Progress

No longer inhibited by the oft-feared sound barrier, aviation was now free to advance. By 1959, the X-15, the X-1’s descendant, would travel five times faster than the speed of sound and pave the way toward human space flight. Yeager and the Bell X-1 rocket plane had proven that an aircraft with passengers could break the sound barrier without injury or harm.

Modern aircraft can reach almost unbelievable speeds and elevations. Take, for example, the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, a sleek and beautiful airplane developed in the 1950s and early 60s to fly quickly and at high altitudes over the Soviet Union. These American military planes were built specifically for reconnaissance missions and feature stealth technology. So, how fast is the SR-71, you ask? It can reach speeds up to Mach 3.3—that’s 2,531 mph. And that means it can travel more than 42 miles per minute.

Hill Aerospace Museum

The Hill Aerospace Museum has a one-of-a-kind Lockheed SR-71C, and so much more. We have more than 70 modern and vintage military aircraft on display, as well as thousands of artifacts representing the history of aviation from the U.S. Air Force, Hill Air Force Base and the State of Utah. And did we mention? Admission to the Hill Aerospace Museum is FREE. Although, voluntary donations do go a long way in helping us maintain our collection of vintage aircraft and vestiges of military history.